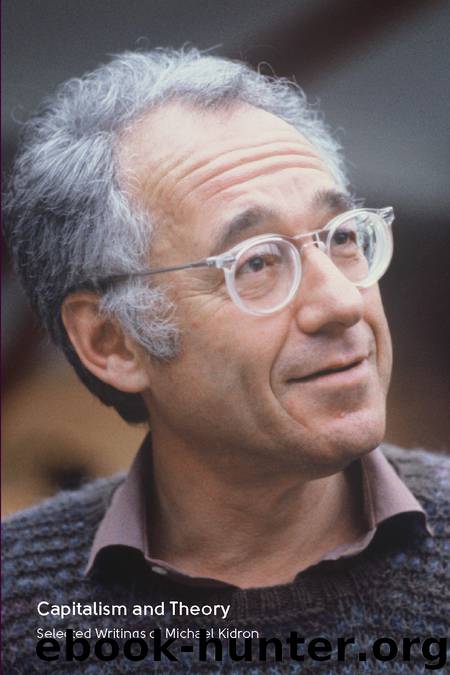

Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron by Michael Kidron Richard Kuper

Author:Michael Kidron,Richard Kuper

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Perseus Books, LLC

Published: 2018-08-29T16:00:00+00:00

Chapter 10

Memories of Development1 [1971]

The economic development of backward countries became a problem in western analysis only after World War II, some time after it had emerged as a problem in practice. Until then the future seemed well taken care of: capitalism would reach into the outermost bounds of the earth in search of raw materials and trade outlets. It would sap the self-sufficiency of the local economies wherever it went and would draw them into systematic contact with the world market.

On occasion, it would be bloody, and civilised men guarding the uncertain marches between purposive violence and brutality might be shamed. But they would not denounce the system for that alone, for the mission it was pursuing with its boots was a civilising one, absolutely in the canon of the classical political economists, relatively in Marx. It was bringing to the entire world the benign influence of capitalism’s superior productivity and leading mankind to a common heritage.

These civilised men were wrong, and by the mid to late 1940s they were said to be wrong, not only by the Marxist and other subcultures of political criticism, but by the main body of academic economists concerned with development.

The capitalist system certainly grew, but not always—not, for instance, during the two world wars and the intervening depression. It did wrench the backward countries into alignment with the world market, but it also stopped them from fully entering it.

The cheap materials that poured out of the modern mining and plantation enclaves in backward countries did encourage further specialisation downstream—in the capitalist heartlands. The demand for equipment, skills and services for use in these enclaves did the same upstream—again, “at home,” not in the host environment. The size of investment, the scale of operation, the experience of social control, all swelled where capitalism was already a going concern.

But everywhere else, indigenous society subsided into increasing agriculturalisation and unemployment, a loss of skills and productivity—a spiral of growing backwardness and poverty. Growing futility, too, since the invasion of capitalism had both destroyed the backward countries’ social and economic integration, and raised the price of entry into the new system beyond their immediate reach.

So, by the end of the 1940s, the academic mainstream had turned interventionist, almost to a man. Academics prescribed, planned, and travelled tirelessly in the cause of policy. They advised governments to harness to domestic “take-off” the development impulses leaking abroad; they pressed for large initial efforts and therefore for state planning and state enterprise; they masterminded a protracted war on the theory and practice of economic liberalism.

They were not agreed on everything. They quarrelled about the extent to which the backward countries could, or should, be protected in the initial stages of their development; the place for foreign capital; the best use of aid; the relative merits of state and private enterprise. More recently a cocky neo-liberal minority has struck out alone, impressed by the seemingly irrepressible growth of world trade and the obvious failure of their colleagues.

But, by and large, the postwar orthodoxy has survived.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(103462)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(11990)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7994)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7671)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7074)

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki(6546)

Pioneering Portfolio Management by David F. Swensen(6264)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(5967)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5749)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4714)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4433)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4260)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4213)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4153)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4151)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3970)

The Dhandho Investor by Mohnish Pabrai(3732)

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai(3708)

Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher(3553)